Stajka Aukst from Zavidovići voted for Jerko Ivanković Lijanović and other candidates of the People’s Party Through Work to Betterment (NSRZB) at the general elections four years ago. She did this on the promise that she would receive money for her vote. She didn’t think at all about how those she voted into power would benefit.

The election results helped Lijanović get the posts of Minister of Agriculture, Waterworks and Forestry and Deputy Prime Minister of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH). That made it possible for him to help pass laws that effect the lives of millions and to dispose of a budget that annually averages 70 million KM.

The Federation Police Authority (FUP) alleges that Lijanović received votes by promising to pay for them and he fulfilled that promise with the money from the FBiH budget. Once in office, Lijanović amended the Program for Agricultural Incentives by introducing one-time subsidies without checks and balances. In this way, almost 3 million KM was dispensed to people who were supposed to vote or agitate for Lijanović’s party.

The police filed a criminal report against him and 56 collaborators charging organized crime and abuse of office. Evidence consists of testimonies from at least 400 persons from FBiH and material evidence such as payment slips, inspections, and advice on how to vote. The complaint was sent to the Sarajevo Cantonal Prosecutor’s Office.

The activists lobbied poor people promising them 100 KM for a vote they would give to the party’s nominees, and to some an additional 20 KM for every additional person that they swayed to vote for them. Aukst, a pensioner, accepted without thinking about the consequences. “On my mind at the time was how to make it better for everyone,” she told the Center for Investigative Reporting in Sarajevo (CIN). She said that she voted for the party’s candidates and Lijanović and won over another 45 voters.According to police, Lijanović organized party colleagues and activists and instructed them how to fish for votes ahead of 2010 elections. He promised them government jobs and 20 KM premiums for each voter that they talked into voting.

The party ranked sixth at the elections in the FBiH and it received five seats in the FBIH Parliament. The party’s vice-president Lijanović received 45,397 votes when running for membership in the BiH Presidency. He failed to secure that office, but he was invited into the Federation government and offered the minister and vice prime-minister posts.

Prime Minister of the FBiH Nermin Nikšić told CIN that during consultations on the make-up the new FBiH government, Lijanović asked to become finance minister. “But, since we turned him down, he settled for the Ministry of Agriculture,” said Nikšić.

Payment of Money

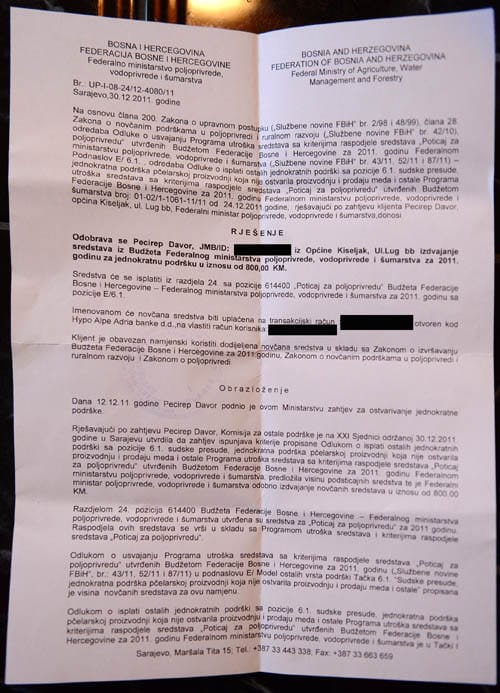

At the time Lijanović became a minister, voters had not received their remuneration. The police investigation found that Lijanović amended the Program of Agricultural Subsidies so that he could pay the voters without anyone watching over his doing so. The FBiH government accepted the changes to the program with a note that this was the minister’s decision. This paved the way for paying out one-time grants of 800 KM.

In the meantime, party activists on the ground were instructing voters how to send in requests for one-time grants to the ministry or were filling them out on their behalf. Aukst said that she did not fill out the grant request herself, but she guessed that somebody from the party did that on her behalf. “I just signed it,” she said.

A photo of an orchard was attached to the request. She said she did not own orchard and lived in a condominium.

Nevertheless, she received an 800 KM agriculture grant. “I got a list of people to whom I was to distribute money and what remained I took myself. I got the list in the party,” said Aukst explaining what happened after the money arrived in her bank account. She kept 90 KM for her vote and 18 KM for each voter that she won over.

“They had promised 20 KM and then it was 18 (KM). Voters were promised 100 (KM) and they cut it to 90. I have no idea why that happened,” she said.

FBiH auditors warned in their 2011 audit of the Ministry that the Law on Subsidies in Agriculture and Rural Development was not envisioned as one-time grants.The grant requests that poured into the Ministry were examined by the Commission for Other Types of Supports. Lijanović appointed to the commission his advisers and party members: Suad Čamdžić, Ana Bašić and Hanefija Topuz, who are also incriminated in the criminal report. According to the report, Čamžić, Bašić and Topuz reviewed the requests and gave a go-ahead even though many were incomplete. Some requests were not even signed.

Lijanović signed off on 3,749 grant requests. The investigation found that the recipients did not keep all the money they received. Most kept the 100 KM they were promised for voting and gave the rest to activists who helped them get grants in the first place. Or, they shared the money with neighbors and family who also voted for the party. Police also found that some of the money was paid for election monitoring and late salaries in the Farmko firm the Lijanović company owns.

Voting Instructions

Kiseljak residents and spouses Danijela and Davor Pecirep who are unemployed and the parents of three children, were among those who received grants. They told CIN how their neighbor Nenad Rajić—the party’s functionary for Kiseljak—asked them if they wanted to earn 100 KM each.

“He brought around documents, ballots. And it was according to numbers – which number we should vote, what do we need to encircle,” Danijela recalls Rajić telling them before the elections. Still, the Pecireps did not want to say if they voted for the party.

CIN has obtained the voters lists from Kiseljak from which it can be seen how one should vote. For example, Davor was instructed to vote at the state level for the party’s nominees Vid Jukić, Sanja Terzić, Ferid Ajanović, Sunita Muslić and Toni Oroz; at the FBiH level for Junuz Brkić, Zdenka Visković, Danijela Misilo and Tanja Kujundžić; at the cantonal level for Karolina Pavlović, Dane Šapin, Blaženka Lukić, Andrea Terzić and Mirela Garić. Numbers were pegged to each candidate.

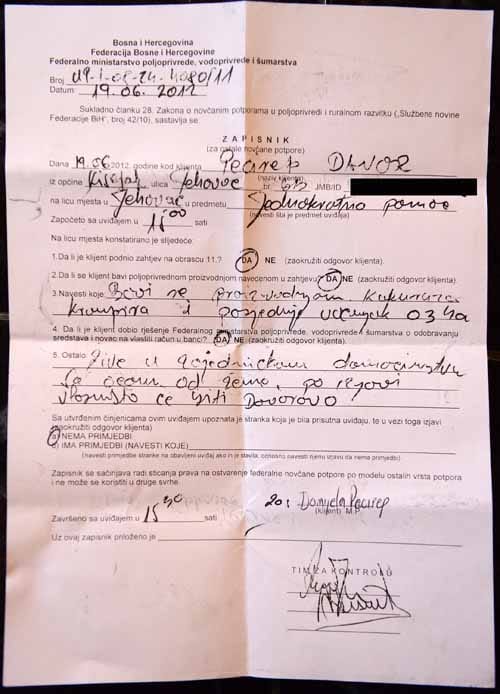

Danijela said that several days after the payment Rajić called again informing them that some people from the ministry were to come as part of an inspection. She said that she was surprised and she did not know what to expect. Commission members asked her “if she sowed” and she replied positively. Several days later, they received via post two grant decisions from the ministry.Danijela said that after the elections she ran into Rajić and asked him where the money was. Several days later Rajić called them to ask if they had opened bank accounts and if they would give him the bank accounts’ numbers, “so that some money can be wired for him and so that he could give them 100 KM each…Not long after that, he called to say—the money cleared (in the bank account), go and take it out,” Davor said. He and his wife each withdraw 800 KM. They said that they gave Rajić 1,400, and kept 200 KM.

“I have no clue what’s going on; I did not ask for a grant,” said Davor. He added that he did not even fill out the request. He believes that this was done by “a person who copied his ID”. “I was in a critical situation. I had to prove that I did not take money, and how was I going to prove it? The party’s management, they’ve planned it and done it shrewdly. They could hide behind the paper they gave to me,” said Pecirep. The couple told police in Kiseljak how they got the money. Then they found out how, along with the request filed on their behalf was a photo of tomatoes. “This is not mine at all,” said Danijela.

Rajić told CIN that his only connection with the grants was in that he helped people get some information. “They’d say: ‘The minister is yours, can you help us?’ Since I took the responsibility to reorganize the Kiseljak (chapter), and we had our minister in the government, I tried to find some information,” said Rajić. His name was on the list of beneficiaries even though he told CIN that he did not receive a grant.

Also on the list is Zlatko Cvjetković from Kiseljak. He told CIN that he did some plumbing for Rajić. Instead of paying Cvjetković for the job he had done, Rajić asked for his and his wife’s bank account numbers. Then he wired 1,600 KM to them. “I don’t know how it happened—through Nenad Rajić. I did not ask for a grant or something. I don’t know who signed it off, but I said that this was not my writing,” said Cvjetković. He kept the agreed money for his services and returned the rest to Rajić. He told that to police who suspect Rajić of promising 100 KM for a vote for the party according to Lijanović’s instructions.

The party’s nominees for the BiH Presidency, the State and the FBiH Parliaments and the Assembly of Central Bosnian Canton won 3,486 votes at 2010 General Elections in the area of Kiseljak where Rajić operated.

In August 2011, Terzić got a job with the Ministry of Agriculture as the head of the Unit for Managing the Project “Supplying Water and Sewerage in the FBiH“. There was no published vacancy for this job opening. Asked how she found about it Terzić said: “When there’s a will there’s a way.”

To Parliament instead of Jail

The police report describes how after the grants were wired, inspection teams from the ministry paid visits to the beneficiaries and lied how everything was fine. Sanja Terzić, the party’s representative in Novi Travnik, was a member of one of these teams. Terzić ran in the last general and local elections, but lost.

The grant beneficiaries from Novi Travnik told the police that the money was given away according to Terzić’s instructions. She denied this: ”It’s all politics. The nationalists don’t really like this party,“ she told CIN. She joined the party in 2009 and she said that she’d always lobby for this party. “No one asked me if my children have something to eat, and Jerko did ask. I can never forget him for that.”

Lijanović told CIN that he had never paid the party’s voters. He said that at the time when he was a legislator with the BiH Parliament he proposed that every citizen going to vote should be rewarded with 100 KM from the state budget. He said that he had sent this motion twice into the parliamentary procedure. Lijanović said that the motion was the reason why some voters expected money: “I met with people who asked me what was going to happen with their 100 KM“.

The FBiH Prime Minister was receiving complaints about the irregularities connected with the payments of agricultural grants. “We as a government have set up a task force which made some investigations and has come up with a series of documents and reports for the police and prosecutors, “Nikšić told CIN.

The Electoral Law in BiH stipulates fines of between 1,000 KM and 10,000 KM for persons and parties who promise money rewards to those who vote for them. Maksida Pirić, a spokesperson for the Central Electoral Commission (CIK) explained that such complaints should have evidence. “Those who might have some findings or some evidence, are free to send them to a respective prosecutor’s office,” he said.

The president of a Tuzla non-governmental organization “Citizen’s Forum”, Vehid Šehić, told CIN that he was aware of vote buying. “Here the elections are considered to be a special type of fight for power, because government is some sort of spoils,” said Šehić.

According to the BiH Penal Code, tampering with voters by way of threat, intimidation, bribe or by taking advantage of their hard economic situation, is punishable by a fine or up to three years in prison. The punishment can be bigger – from six months to five years in prison – for an election official.

Samardžić never served that time. His sentence was commuted into a fine of 18,000 KM. Nowadays he’s the party representative in the FBiH Parliament. Samardžić told CIN that in 2010, the party’s presidency offered him a compensatory term as he was a businessman. He accepted. “I became a party member after the 2010 elections. I was not in the party’s headquarters at those elections, nor was I talking to media or posters…,” said Samardžić. He said that he was found guilty based on the testimony of Nisvet Duratović who said they had collected votes together. Duratović pleaded guilty to bribing and tampering with voters and was sentenced to probation.Hasan Samardžić from Cazin was sentenced before the state court for illegal lobbying of Party for Betterment’s voters in 2010. The court fined him 4,000 KM and sentenced him to six months in jail at the end of May 2013 for “violating voters’ freedoms”.

Samardžić said that after all of this he hopes for another compensatory term. “I hope that just now the party won’t forget me.“

Participation in the election irregularities has not harmed the party’s other activists. Out of 57 incriminated persons in the report, at least 20 were the party’s candidates in the latest elections in 2012. Some of them have gone into government.